Chapter 1

Beauchamp the Builder

I

will that when it liketh to God, that my Soule depart out of this

World, my Body be interred within the Church Collegiate of our Lady in

Warwick, where I will that in such Place as I

have desired, (which is known well) there be made a Chappell of our

Lady, well, faire and goodly built; within the

middel of which Chappell I will that my Tombe be made…Also, I wish that

there be said every Day, dureing the Worlde, in

the aforesaid Chappell that (with the Grace of God) shall be thus new

made, three masses…

The extract above is part of the Last Will and Testament of one of the

most important men in the early years of the 15th century. Richard

Beauchamp was born on 28th January, 1382, at

Salwarpe, near Droitwich in Worcestershire. His father Thomas, a

soldier and politician of considerable influence,

was also tutor and Guardian to King Richard II.

On Thomas’s death in 1401 the nineteen-year-old Beauchamp became 13th

Earl of Warwick and soon began to carve out a considerable reputation

for himself. For the part he played

in defeating the Welsh rebel Owen Glendower, Beauchamp was made a

Knight of the Garter, the height of

medieval chivalrous honour. His other exploits included a two-year

pilgrimage to the Holy Land. A late

fifteenth-century document, The Pageant of the Birth, Life and Death of

Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, which

details his travels in depth, is now in the British Museum, although

David Brindley warns against assuming that this

document consistently relates reliable historical detail.

In 1410, Beauchamp became a member of the council charged with

governing the country during the indisposition of King Henry IV, and

remained involved in politics at the highest

level as a senior member of the royal household for the rest of his

life. This included playing a key role in the

dispute with France. Following the King’s death, Henry’s son came to

the throne as Henry V and in 1420 Beauchamp arranged

Henry’s marriage to Katherine, daughter of Charles VI of France.

Tradition has it that in 1422 Henry V, on his

deathbed, gave his son Henry VI into the care of his close friend and

companion Beauchamp. As Henry VI was still very

young, it fell to the Council to ensure the security of the Kingdom and

this included dealing with the French

problem. Beauchamp returned to France where he was appointed to the

command of Rouen and was the authority

presiding over the trial and martyrdom of Joan of Arc.

Beauchamp returned to England in 1427, to become ‘head of a financial

and land holding which was, by the 1430’s, among the richest in

Europe’. This he had achieved through a

combination of shrewd management, inherited estates, two advantageous

marriages as well as from ransoms and the

spoils of war However, some five years later he was appointed by the

young King to the post of Lieutenant of the

English Dominions in France. Having made his Last Will and Testament,

written just prior to his final departure for

France, Beauchamp died in the castle at Rouen on 30th April 1439 aged

fifty-eight.

It would appear from his Will that Beauchamp had given some

considerable thought to his final resting place, and the wealth he had

accrued enabled him to insist that his memorial would

be one that reflected his position in society. However Brindley

maintains that it is unlikely that it is

possible to deduce anything of Beauchamp’s personal faith in the

magnificent edifice that his wealth enabled him

to plan, claiming that ‘the concept of personally chosen faith would

have been incomprehensible to someone of Beauchamp’s

time’. Similarly Doreen Rosman sees the Christian faith as ‘not

something individuals chose but something

they were born into, an integral part of the texture of society’. Eamon

Duffy, while accepting that ‘among the

higher gentry at least there were signs of a privatising tendency’,

such as the growing proclivity to secure for

themselves private chaplains and devotional treaties, nevertheless

maintains that:

the

overwhelming impression left by the sources for late medieval

religion in England is that of a Christianity resolutely and

enthusiastically orientated towards the public and the

corporate, and of a continuing sense of the value of co-operation and

mutuality in seeking salvation.

Nevertheless, there was evidence of a burgeoning belief in the need for

personal repentance. Manuals that aided personal devotion, such as the

Meditations Vitae Christi circulated

widely, and the influence of the preaching order of Dominican friars

had spread throughout the country. Beauchamp did

own a volume, now known as the Trevisa Manuscript, which included

debates on the nature of spiritual and

temporal power, but the tone of the writing was staunchly defensive of

the established Church, denigrating the impact

of such innovations as the preaching friars.

This conservative outlook is reflected in the fact that, although

Beauchamp’s Lady Chapel was certainly a private Chapel, elements such

as the space itself, the windows, the statuary,

the paintings, the tomb itself and the provisions Beauchamp made for

masses to be said within it, are pointers

which reveal much about the piety of the time which emphasised the

acquisition of virtues for the salvation of

souls, and it is these components that will be explored in this chapter.

Architectural Space

The footprint of the Chapel is large compared to most existing chantry

chapels attached to churches in England. Its size and architectural

grandeur not only reflects the status of

Beauchamp as ‘among the greatest English nobles of the Middle Ages’,

but also echoes the 13th century belief that

religious buildings were considered to be, ‘representation[s] of the

heavenly Jerusalem, the ideal city according

to the Apocalypse’.

For Lawrence Lee, ecclesiastical buildings of the medieval time were

also spaces in which those who entered, ‘embarked on a spiritual

journey akin to pilgrimage, a journey dictated

by the symbolic structure of the journey.’ Since earliest Christian

times, the priest and congregation faced east

in the direction of the rising sun, awaiting the Second Coming of

Christ. On the north side, associated with darkness,

cold, and evil, were placed elements from the Old Testament, whereas

New Testament narratives were placed on the

light south side. Decorative elements on the west side, associated with

humanity, typically featured

iconography designed to remind the faithful that, just as they entered

this Church, the time would come when they would face

judgement on entering the next world.

he Beauchamp Chapel also appears to have followed these principles.

The inner east façade was adorned with elements portraying

Christ, the heavenly hierarchy and some chosen

saints – a view that Beauchamp, who with his family were also portrayed

in the east window, would hope to see at the

Second Coming. On the west wall of the Chapel the large ‘doom’ painting

executed by John Brentwood in 1449,

illustrated the final judgement which would see the Godly going to

Heaven, and the Godless being consigned to Hell.

This sombre painting served as a constant reminder of the cosmic

context of life on earth and a warning

of the possible fates that awaited each individual in the afterlife.

Because of subsequent damage it is difficult to know with certainty

whether the device of placing Old Testament iconography on the north

wall and that depicting New Testament material

on the South wall was followed. However Elsie Kibble maintains that the

quotations in the middle window on the

north side suggests that the figures on the North wall are likely to

have been the Old Testament prophets Hosea,

Joel, Amos, Obediah, Micah, Habbakuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah and

Malachi. She also speculates that the

South windows would have contained material from the New Testament,

such as an Annunciation Scene with

images of the Virgin Mary and St. Elizabeth.

Although specific parallels between the Church’s teaching and the

stories that appeared on the walls are hard to track down, painted

frescoes were not only to teach Christian truth as

it was understood, but also to improve people’s behaviour through moral

instruction and example. Besides the

popular depiction of the Last Judgement, other subjects such as ‘The

Seven Works of Mercy’, Saints and angels

also found favour. By contrast, paintings of Christ’s earthly ministry

appear to have been less widespread and

surviving examples are very rare. The Church may have permitted

painting as a means of instruction and edification but

this was hedged around with certain conventions. To confuse the piety

of the simple by innovations and

individual impulses was considered a serious matter.

The Iconography of

the

Chapel

The Iconography of

the

Chapel

Besides the positioning of religious artefacts around the chapel,

the

painted stone figures, the images depicted in the stained glass and the

wall paintings were all seen as fulfilling a

function according to medieval symbolic theological beliefs.

Unfortunately the wall paintings have not

survived, with the exception of one faint rendering of an angel. The

stained glass also sustained considerable damage but

almost half of the East widow survived to give an insight into the

spiritual mindset of the late medieval world.

For instance, the figures in the East window depicting the saints had

huge significance. Indeed, Emile Mâle considers ‘it may well be

that the saints were never better loved than

during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries’. From carvings on the

gable-ends of houses, to lavish colourful images

that filled the churches, they were a constant reminder of an unseen

but very potent world. Not only were saints’ days

times of feasting in the Christian calendar, saints per se also

fulfilled other functions. They were seen first and

foremost as ‘friends and helpers’ In return for devotion, not to be

confused with the worship afforded to Christ, the

saint would pray for the client during life, continuing to pray for the

soul of their patron after death thus

reducing time in purgatory and interceding for them at the Last

Judgement.

This devotion also included a veneration of items associated with their

heavenly protector. For medieval Christians, contact with tangible

relics of Christ and the saints provided a unique

bridge between earth and heaven. Such relics were seen as a way to come

closer to the saints and thus form a closer

bond with God. Some relics were body parts, such as a bone, but more

often they were everyday items such as

a small piece of cloth that had been used by the venerated one or even

a fragment of a item with which they had

been in contact. The relics housed in St. Mary’s, probably in a small

vestry behind the Chapel altar, included:

Part

of the chair of the patriarch Abraham, the burning bush of Moses

and the manger in which Jesus was laid; of the pillar to which he was

bound when he was scourged; a thorn from His

crown, a piece of the cross; part of the towel in which His body was

wrapped by Nicodemus; some hair of the

Virgin Mary, bones of the Innocents and part of the penitential garment

of St. Thomas, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Such was the veneration of relics that individuals often

undertook

pilgrimages to shrines of holy people where they could view objects

associated with the saints, often purchasing a badge

or memento as a means of acquiring something of the spiritual

protection of the saint.

Medieval spiritual and secular life was closely interwoven, and both

incorporated a rigid hierarchical system. On earth ‘In principle there

were two kinds of authority…the spiritual

authority of which the pope was head, and the temporal authority of

emperors and kings and lesser potentates’. In the

spiritual realm the order of precedence was Pope, archbishops, abbots,

archdeacons and canons; then at the bottom

of the pile the parish clergy and the clerical rank and file. There was

a corresponding division throughout

society leading down from emperors to kings, princes, great lords,

knights and, a great way below, peasants.

Therefore it is hardly surprising that this concept of class-system was

also seen as applying to the heavenly realm, with the

idea of having intermediaries to approach God being not only

appropriate but essential.

The saints Beauchamp

chose to include in the East window of his Chapel

were all British Saints being the Royal Saint Thomas of Canterbury,

Saint Alban, Saint Winifrid of Wales and

Saint John of Bridlington. The reasons for all of these choices are not

recorded but Brindley believes that they all

held some significance for Beauchamp. St. Thomas was a Saint of

international reputation who upheld the notion of

chivalry in that he was martyred for resisting the King’s attempts to

curtail the power of the Church.. St.

John of Bridlington was closely associated with Henry V’s court of

which Beauchamp was a member and indeed the King’s

victory at Agincourt was attributed to the aid given by that particular

saint. Richard himself had recovered

from an illness at the town of St. Albans, and St. Winifid of Wales was

the Patron Saint of the church in Shrewsbury

where he had received his Garter. Such was his devotion to these saints

that Beauchamp bequeathed a gold statue of

himself to each Monastic house patronised by these four saints, all of

which survive in their original

form.

The saints Beauchamp

chose to include in the East window of his Chapel

were all British Saints being the Royal Saint Thomas of Canterbury,

Saint Alban, Saint Winifrid of Wales and

Saint John of Bridlington. The reasons for all of these choices are not

recorded but Brindley believes that they all

held some significance for Beauchamp. St. Thomas was a Saint of

international reputation who upheld the notion of

chivalry in that he was martyred for resisting the King’s attempts to

curtail the power of the Church.. St.

John of Bridlington was closely associated with Henry V’s court of

which Beauchamp was a member and indeed the King’s

victory at Agincourt was attributed to the aid given by that particular

saint. Richard himself had recovered

from an illness at the town of St. Albans, and St. Winifid of Wales was

the Patron Saint of the church in Shrewsbury

where he had received his Garter. Such was his devotion to these saints

that Beauchamp bequeathed a gold statue of

himself to each Monastic house patronised by these four saints, all of

which survive in their original

form.

Returning to the composition of the East Window; it is not possible to

ascertain with any certainty the configuration of the lower panels.

However, it is likely that the figure of the

Virgin Mary, to whom the chapel was dedicated, and who inspired the

deepest devotion in late medieval England, took pride

of place in the middle of the window in the original glazing scheme.

The cult of Mary came second only to that of Christ himself and

‘towered above that of all the other saints’ ‘The Five Joys of Mary’

formed the subject matter for many prayers and

meditations. There were many statues of Mary with the most common

portrayal being that which was displayed in the

rood screen of most churches showing Mary with St. John standing one at

each side of the cross. This scene served

as a reminder of the Sorrows of Mary, the ‘Mater Dolorosa’, which could

act as a bridge between her and any of

her devotees who themselves were experiencing the sorrows of the death

of their loved ones through such

calamities as the plagues. This also enabled them to metaphorically

stand beside Mary and share in her sorrows at

the death of their Saviour.

The manifestation

of this link can be seen in the words of the ‘Obsecro

Te’, a lengthy prayer to the Virgin contained within the Horea, which

Duffy maintains ‘quickly found favour with the

laity’. The final section of the prayer speaks of the benefits that

could be accrued through the intercessions of Mary.

Some of these could be enjoyed during earthly life but by far the

greatest was ‘the spiritual gifts a

Christian requires to get to Heaven’. For, if Christ is really judge

and arbiter at the end of time, who better than his Mother to

intercede for a human sinner. Therefore it is hardly surprising that

the effigy of Beauchamp lies with his hands

slightly apart so that he can clearly see the figure of Mary looking

down from a boss in the ceiling above his head.

The manifestation

of this link can be seen in the words of the ‘Obsecro

Te’, a lengthy prayer to the Virgin contained within the Horea, which

Duffy maintains ‘quickly found favour with the

laity’. The final section of the prayer speaks of the benefits that

could be accrued through the intercessions of Mary.

Some of these could be enjoyed during earthly life but by far the

greatest was ‘the spiritual gifts a

Christian requires to get to Heaven’. For, if Christ is really judge

and arbiter at the end of time, who better than his Mother to

intercede for a human sinner. Therefore it is hardly surprising that

the effigy of Beauchamp lies with his hands

slightly apart so that he can clearly see the figure of Mary looking

down from a boss in the ceiling above his head.

Many of the painted stone figures surrounding the East window also

remain almost as they were when they were placed there. They include

God, at the apex of the window seated upon a

throne, with the ‘thrones’ – one of the nine orders of angels – on each

side of him. These figures are a

remarkably complete survival of the careful iconography of the chapel

and are considered as an extension of the

window glass. This heavenly hierarchy continues down the borders and

mullions featuring the other eight

orders, seraphim, cherubim, virtues, powers, dominations, angels,

including the Angel of the Expulsion the

archangels Michael and Gabriel, and principalities, along with the

shields of the Beauchamps and their connections.

The larger stone saints surrounding the window are, on the north side,

St. Barbara who has the tower in which she was imprisoned in one hand

and a book in the other, and St. Catherine,

not with a wheel but with the sword used to behead her. On the south

side, St. Mary Magdalene holds the pot of

ointment with which tradition suggests she anointed Christ and St.

Margaret of Antioch stands on Satan in the

shape of a dragon who, according to legend, swallowed her. Again we

have no indication as to the reasons for their

inclusion, but one interesting idea put forward by Brindley is that

there may be something significant in the

inclusion of St. Barbara and St. Catherine – the two voices heard by

Joan of Arc! Whether this might have been due to

guilt, recompense or as ‘insurance’ against the anger of the Saints is

open to speculation.

Yet it was not just

the spiritual realm that was featured in the

window. The traceries, still in their original form, contain not only

seraphims and the Gloria, but also scrolls or pennants

with the words ‘Louez Spencer – tant que vyray’. In addition Kibble

believes that the subject matter in the

lowest portion of the window was Beauchamp himself, flanked by his two

wives Isabella Despencer and Elizabeth

Berkeley, his son Henry, and his daughters Anne, Margaret, Elizabeth

and Eleanor. While pointing out that the

religious imagery should not be viewed as mere decoration but ‘visible

proof of the presence of saints and their

intercessory powers’, Roffey also acknowledges that the fabric of

chantry chapels was also intended to ‘create potent

symbols of personal and corporate prestige, piety and influence’.

Yet it was not just

the spiritual realm that was featured in the

window. The traceries, still in their original form, contain not only

seraphims and the Gloria, but also scrolls or pennants

with the words ‘Louez Spencer – tant que vyray’. In addition Kibble

believes that the subject matter in the

lowest portion of the window was Beauchamp himself, flanked by his two

wives Isabella Despencer and Elizabeth

Berkeley, his son Henry, and his daughters Anne, Margaret, Elizabeth

and Eleanor. While pointing out that the

religious imagery should not be viewed as mere decoration but ‘visible

proof of the presence of saints and their

intercessory powers’, Roffey also acknowledges that the fabric of

chantry chapels was also intended to ‘create potent

symbols of personal and corporate prestige, piety and influence’.

Kenneth Hyson-Smith sees the Church in England in 1384 as being ‘firmly

established as the second power in the land after the Crown, and

arguably without equal in the

comprehensiveness and complexity of its institutional organisation’.

There were some rising signs of anti-clericalism and

anti-papalism, with Gayk seeing this period as marking a significant

shift: ‘In England for the first time arguments

against images were being put forth by lay men and women in the

vernacular’. Nevertheless, despite these signs of

disaffection, this was still a time of relative secular and

ecclesiastical order so it would have seemed appropriate

that ecclesiastic elements such as the saints should be portrayed side

by side with Beauchamp and his family in the

window. Indeed, it was an example of the connection that still existed

between piety and power; God was King

over all, but on earth the King was still God’s chosen one and his

representative on earth.

Not only were the subjects in the windows symbols of magnificence, but

so was the high quality of the material and workmanship of the stained

glass. All of the windows were commissioned

from John Prudde of Westminster, Henry VI’s own Royal Glazier. The

covenant states that;

John

Prudde doth covenant to glass all the windows in the new Chapel in

Warwick with glass beyond the seas, and with no glass of England. It is

to be the strongest glass and of the

finest colours of blue, yellow, red, sanguine, purpure and violet, so

to make rich and embellish the matters, images

and stories…

These were to be

newly traced and pictured by another painter employed

by Prudde, and from these the stained glass was to be executed. As

little as possible of green, white and

black were to be used as these were considered inferior. Prudde himself

was to take charge of the glass when wrought

and set it up in the chapel windows. For this he was paid two shillings

a square foot – a very considerable sum

considering that the usual charge for glass was between 7d. and 1

shilling even for prestigious buildings. Indeed, the

elaborate windows given by Henry VI to Eton College only cost 1s 4d per

square foot. The final cost of the windows

was about £100.

These were to be

newly traced and pictured by another painter employed

by Prudde, and from these the stained glass was to be executed. As

little as possible of green, white and

black were to be used as these were considered inferior. Prudde himself

was to take charge of the glass when wrought

and set it up in the chapel windows. For this he was paid two shillings

a square foot – a very considerable sum

considering that the usual charge for glass was between 7d. and 1

shilling even for prestigious buildings. Indeed, the

elaborate windows given by Henry VI to Eton College only cost 1s 4d per

square foot. The final cost of the windows

was about £100.

However the windows have more to reveal than just the status of the

Earl. For example the Tracery Lights on the side windows hold clues

regarding worship in the Chapel. The two pairs

situated closest to the altar show angels playing fifteenth century

instruments, which are of great interest to

students of early music, while the other four windows depict angel

musicians with scrolls some of which contain

music. One work is ‘Gaudeam omnes in domina, diem festum celebrantes’,

referring to the Festival of the Assumption

of the Virgin Mary. This was sung in antiphonal form as an introit at

the beginning of Mass and Kibble

speculates that it was also sung as Beauchamp was lowered into his

tomb. What is sure is that music, under the

patronage of Beauchamp, was very important within his household.

Two composers were employed by him, Robert Chirbury and John Soursby

both of whom had also served in the Royal Household Chapel in Rouen.

Alexandra Buckle argues that the

polyphonic music played in the Chapel may well have been written by one

of these two late medieval composers.

According to Buckle:

Beauchamp’s

specification of Lady Mass ‘with note’ is a reminder that

he had been an avid patron of music…His executors thus designed a space

for him that celebrated music…They went

further by including substantial musical iconography in his final

resting place.

The Tomb

The quality of all

of the ornamentation in the Chapel indicates the

wealth and power of Beauchamp. The total cost for the Chapel was

£2,400 but the structure that dominated the

Chapel, the Tomb, added an extra £720 to that sum. Elements in

the construction of the tomb including its position,

composition, iconography and motto can be seen as echoing the piety of

the age.

The tomb was placed,

in accordance with the tradition of the time,

close to, and immediately in front of the focus of power – the altar.

Roffey maintains that ‘Burial close to the altar

forged a connection with the mass and its implicit intercessory

efficacy and highlighted one’s tomb or memorial to those

participating in the mass’.

The tomb was placed,

in accordance with the tradition of the time,

close to, and immediately in front of the focus of power – the altar.

Roffey maintains that ‘Burial close to the altar

forged a connection with the mass and its implicit intercessory

efficacy and highlighted one’s tomb or memorial to those

participating in the mass’.

The materials chosen for the tomb were of the highest quality as

befitted one whose status in the earthly hierarchy was in the highest

echelons. The step and the top of the elaborately

carved chest was a slab of Purbeck marble, a material Linda Monckton

claims was:

a

prestigious one and was selected for the great reredos screen of

contemporary date in Westminster Abbey and was used for the chests of

Edward III and Richard II in their

Westminster tombs, the latter precedent for the design of Beauchamp’s

own tomb chest.

It is John Essex who is usually recorded as having carved the tomb, but

other sources indicate that it was a collaboration between Essex, who

worked from St. Paul’s Churchyard in

London, and John Bourde of Corfe who is also mentioned in the original

contract for the tomb.

On the top of the tomb lies Beauchamp’s life-size effigy, believed to

be the only cast-metal effigy of a non-royal figure before the

sixteenth century. This was cast by William Austen of

London in latten, an alloy similar to bronze, and covered in gold by

Bartholomew Lambspring assisted by Roger Webbe,

a barber whom Brindley speculates may have been included due to his

surgeon’s knowledge of anatomy, and

John Massingham, ‘a kerver’ [carver].

Brindley posits

that

is it unlikely that the effigy is an accurate

portrait, and that ‘The armour is of a style first made in Milan more

than a decade after Beauchamp’s death, and so could not have

been his own.’ This may very well be so, yet the intricate details,

such as the raised veining on the hands

indicate a desire for a high level of accuracy. Perhaps the effigy was

based on a lost portrait of Beauchamp as a young

man, for it does seem to be a likeness of someone and a desire for

exactitude would resonate with the growing

desire at that period to represent accurate physical features. Whereas

in the Romanesque Art of the early Middle

Ages faces lacked individualism and were even interchangeable, late

Medieval artists, sculptors and painters

began to embrace the Gothic style which was beginning to portray

individual features. This gave rise to the

flowering of Renaissance Art. This puzzle is one to which a solution is

unlikely to be found.

Brindley posits

that

is it unlikely that the effigy is an accurate

portrait, and that ‘The armour is of a style first made in Milan more

than a decade after Beauchamp’s death, and so could not have

been his own.’ This may very well be so, yet the intricate details,

such as the raised veining on the hands

indicate a desire for a high level of accuracy. Perhaps the effigy was

based on a lost portrait of Beauchamp as a young

man, for it does seem to be a likeness of someone and a desire for

exactitude would resonate with the growing

desire at that period to represent accurate physical features. Whereas

in the Romanesque Art of the early Middle

Ages faces lacked individualism and were even interchangeable, late

Medieval artists, sculptors and painters

began to embrace the Gothic style which was beginning to portray

individual features. This gave rise to the

flowering of Renaissance Art. This puzzle is one to which a solution is

unlikely to be found.

During the medieval period the link between the earthly kingdom and the

heavenly kingdom also found expression in myths and legends of the

fight between good and evil. The heavenly

war, as portrayed in the Scriptures, was also to be fought on earth.

This not only involved participation in the

Crusades, but also encouraged warriors to imitate the heroes who

engaged in holy quests such as that involving the Holy

Grail. Brindley maintains that the illustrations in the Pageants are

meant ‘to portray Beauchamp as a knight in the

chivalrous tradition’. This may be the reason that Beauchamp’s head

rests on a swan, part of the Beauchamp crest,

which Brindley maintains implies descent from the legendary hero

Lohengrin who appears in much medieval folklore

and literature. Although such a claim on the part of Beauchamp appears

to have been based on no known fact, it

was a common one associated with more than one noble family, and

represented in English literary tradition by

the late fourteenth-century verse romance Chevelere Assigne. Perhaps

the notion of claiming some connection with

such a noble Knight was irresistible to one considered by Brindley, to

be ‘one of the last great figures of

chivalry’.

Another possibility is that Beauchamp was claiming kinship with the

family of Godfrey of Bouillon, a medieval Frankish knight who was one

of the leaders of the First Crusade. After

the successful siege of Jerusalem in 1099, Godfrey became the first

ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, although he

refused the title ‘King of Jerusalem’ as he said that title belonged to

God. Idealised in later accounts, Godfrey

was included among the ideal knights known as the Nine Worthies. In

fictional literature, Godfrey became the hero of

numerous French ‘chansons de geste’ dealing with the crusade. By the

12th century, Godfrey was already a legend

among the descendants of the original crusaders. This may be no nearer

the truth than the story connecting

Beauchamp directly with Lohengrin, yet if there was no bloodline

relationship with these heroes of old, Beauchamp

certainly claimed descent from Guy of Warwick.

Guy, now also known to be a legendary character, was a hero of the

Romance genre. The story goes that Guy fell in love with the lady

Felice who was of much higher social standing. In

order to wed her he had to become a knight and to achieve this he

needed to prove his valour in chivalric

adventures which included battling fantastic monsters such as dragons,

giants, a great boar and the Dun Cow. He succeeded

and, on his return, wed his lady. However, full of remorse for his

violent past, he embarked on a pilgrimage to

the Holy Land. Eventually he returned privately and lived out the rest

of his life as a hermit in a cave overlooking

the River Avon at a location still called Guy’s Cliffe.

‘Guy’s sword’ remains on show in Warwick Castle but Beauchamp’s effigy

in the Chapel also bears a sword appropriate to his status. Another

feature of the effigy which bears

witness to Beauchamp’s status in the temporal hierarchy is that, while

under his right foot is the Beauchamp bear,

under his left foot is the Despenser griffin of his second wife Isabel

Despenser. This denoted his position of importance

within both prominent aristocratic families.

Nevertheless, despite all these knightly attributes, the fact that the

position of Beauchamp’s hands allow him to gaze upwards to the figure

of the crowned Queen of Heaven emphasises

that, although the Chapel may have become known as the Beauchamp

Chapel, for Beauchamp it was also

dedicated to the most powerful Saint available to intercede for him in

the afterlife and he wished to keep

his eyes firmly fixed on her. The whole effigy is surrounded by a

cage-like construction built to support a fabric cover,

tapestry or velvet, called a ‘hearse’, which would have been removed to

reveal the effigy only when mass was said

for his soul.

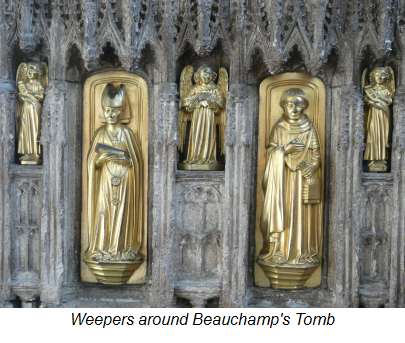

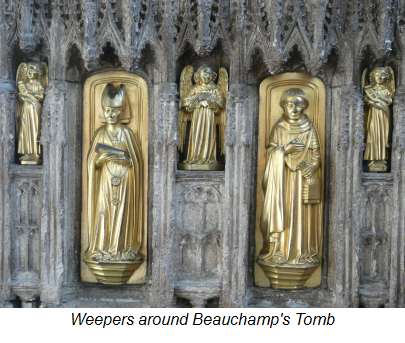

Around the sides of

the tomb were set niches containing fourteen

figures or ‘weepers’ interspersed with angels and miniature bears and

ragged staffs. The figures were cast by William

Austen of London in latten, an alloy similar to bronze and covered in

gold. Weepers were living people who would mourn

the death of the person in the tomb and whose intercessions could add

weight to those of the saints. On one

side of Beauchamp’s tomb are female weepers and on the other side are

male weepers – all of them notable

members of Beauchamp’s family and the nobility, and each identifiable

from the enamelled coats of arms around

the base.

Around the sides of

the tomb were set niches containing fourteen

figures or ‘weepers’ interspersed with angels and miniature bears and

ragged staffs. The figures were cast by William

Austen of London in latten, an alloy similar to bronze and covered in

gold. Weepers were living people who would mourn

the death of the person in the tomb and whose intercessions could add

weight to those of the saints. On one

side of Beauchamp’s tomb are female weepers and on the other side are

male weepers – all of them notable

members of Beauchamp’s family and the nobility, and each identifiable

from the enamelled coats of arms around

the base.

‘Medieval society was a hierarchy, and the orders of the heavenly host

resembled the earthly society’. Therefore, just as Mary because of her

high status as Queen of Heaven, was placed

higher – and thus potentially given more power – than the apostles,

evangelists and universal saints, it is

possible that Beauchamp considered that having all those highly placed

human individuals to mourn him would reduce his

time in purgatory considerably. Nevertheless, by the time the Earl was

finally installed in his resting place, his

son Henry and Henry’s wife Cecily were themselves dead.

The inscription around the tomb is interesting in that it is in

English. Sir William Dugdale, quotes Beauchamp as requesting that ‘In

the two long plates they shall write in latine in

feine manner all such Scripture of Declairation as the said Executors

shall devise’. However, it would appear that his

executors were prepared to deviate from this instruction as Brindley

considers that the final inscription is

probably the first monumental eulogy written in the English language.

This was a reflection of the growing use of the

mother tongue in ecclesiastical and secular affairs rather than the

more conventional French. Indeed between 1360 and 1400

English replaced French in the army and Law Courts, and in 1348 English

became the medium for teaching in

the schools. The text of the inscription around the tomb reads:

Prieth

devoutly for the sowel whom God assoille of one of the moost

worshipful knightes in his dayes of manhode and conning, Richard

Beauchamp, late Eorl of Warrewik Lord Despenser of

Bergevenney and of mony other grete lordships whos body rcsteth here

under this tombe in a fulfeire vout of

stone set on the bare rooch. The which visited with longe siknes in the

castel of Roan therinne decessed ful

christenly the last day of april the yer of our Lord God A.D.

MCCCCXXXIX he being at that tyme lieutenant genal and

governor of the royalme of Fraunce and of the duchie of Normandie by

sufficient autoritie of our sovaigne lord

the king Harry VI. The which body with grete deliberacon and ful

worshipful conduit bi see and by lond was broght to

Warrewik the III day of October the yer above seide and was leide with

ful soleime exequies in a feir chest

made of stone in this churche afore the west dore of this chapel

according to his last wille and testament therin to

reste til this chaple by him devised in his lief were made. Al the

whuch chapel founded on the rooch and alle membres

therof his executors dede fully make and aparaille by the same

auctorite the dide translate fful worshipfully

the seide body into the voute aboveseide. Honorid be God therfore.

Here too we have an indication of the ties between the spiritual and

the temporal for, despite the injunction to pray for Beauchamp’s soul,

it would appear that it was his knightliness

rather than his piety that is emphasised here.

The foundation stone of the Beauchamp Chapel was laid in 1443, some

four years after Beauchamp’s death, with the building and its

decoration being completed in 1460. However

Beauchamp’s body was not moved from the position by his father into the

tomb built for him until some fifteen

years later. As his remains were placed into the tomb the presiding

Bishop offered up the prayer that, just as God had

wished the bones of Joseph, son of Israel, to be taken on the

wanderings by the Israelites until they found their

resting place in the Promised Land, so the bones of Beauchamp, could at

last have their final resting place in the

magnificent Chapel just as he had planned. Thus, once again the link

between Beauchamp’s temporal status and that of an

Old Testament hero was seen as comparable.

Provisions for the

Chantry Masses

As previously mentioned, a chantry was a service rather than a place,

based on an unquestioning belief in the intercessory role of the

saints, the need to offset the perils of

purgatory by good works and the duty to provide for the spiritual

well-being of this family. Having engaged with the first

by the placing of saints in the Chapel, the second by the funding of

the Chapel, it was necessary to ensure that the

spiritual welfare of Beauchamp and his family did not go astray.

St. Mary’s had been a Collegiate Church, served by a Dean and canons

since 1123 when Henry, 1st Earl of Warwick, had begun the foundation of

the college by the establishment

of one prebend, which was an endowment providing income for one canon.

Henry’s son Roger had given sufficient

property for the maintenance of six other prebends. The small community

came together daily to celebrate Mass and

the seven canonical offices.

Beauchamp’s will specified four daily masses to be celebrated in his

chapel to secure his soul and the souls of his family, two to be Masses

of the Dead, and the third a Mass following

the weekly votive cycle. However, the fourth was the Lady Mass that

Beauchamp especially asked to be ‘with note’.

Provision was thus made for three chantry priests to sing the masses

‘for ever’. Rather than just an act of

religious individualism, this indicated a piety that acknowledged

communal responsibility. Roffey maintains that, not only

the individual benefited from the quantity of prayers as they ‘more

powerfully enhanced the intercessory element of

the ritual’, but that ‘the laity, in turn, benefited from even more

elaborate and plentiful ceremonies and the

spiritual efficacy of the mass itself.’ This he maintained was due to

the fact that the laity ‘sustained an inherent

feeling of spiritual and psychological security from it’.

However the desire of Beauchamp for chantry masses to be celebrated in

perpetuity was not fulfilled, for the world-order Beauchamp had served

was quickly passing and the power once

assumed by such magnates was in decline. Within two or three

generations of his death, the medieval

order came to an end. Politics, the Royal succession, the unwillingness

of some sections of the population to

unquestioningly obey the edicts of Papal authority, and the

proliferation of printed literature, all made a

contribution to the chaos that was to herald the Reformation. These

forces were to make a significant impact on the

system Beauchamp had put in place for the good of his soul for, within

seventy-five years of his being ensconced

in his magnificent tomb, the voices had ceased by order of the King.

All text and illustrations on this

site are

©

Doreen Mills - 2012

This page was last updated on 9th February 2013

If you have any comments or queries please contact

Doreen

The Iconography of

the

Chapel

The Iconography of

the

Chapel The Iconography of

the

Chapel

The Iconography of

the

Chapel The saints Beauchamp

chose to include in the East window of his Chapel

were all British Saints being the Royal Saint Thomas of Canterbury,

Saint Alban, Saint Winifrid of Wales and

Saint John of Bridlington. The reasons for all of these choices are not

recorded but Brindley believes that they all

held some significance for Beauchamp. St. Thomas was a Saint of

international reputation who upheld the notion of

chivalry in that he was martyred for resisting the King’s attempts to

curtail the power of the Church.. St.

John of Bridlington was closely associated with Henry V’s court of

which Beauchamp was a member and indeed the King’s

victory at Agincourt was attributed to the aid given by that particular

saint. Richard himself had recovered

from an illness at the town of St. Albans, and St. Winifid of Wales was

the Patron Saint of the church in Shrewsbury

where he had received his Garter. Such was his devotion to these saints

that Beauchamp bequeathed a gold statue of

himself to each Monastic house patronised by these four saints, all of

which survive in their original

form.

The saints Beauchamp

chose to include in the East window of his Chapel

were all British Saints being the Royal Saint Thomas of Canterbury,

Saint Alban, Saint Winifrid of Wales and

Saint John of Bridlington. The reasons for all of these choices are not

recorded but Brindley believes that they all

held some significance for Beauchamp. St. Thomas was a Saint of

international reputation who upheld the notion of

chivalry in that he was martyred for resisting the King’s attempts to

curtail the power of the Church.. St.

John of Bridlington was closely associated with Henry V’s court of

which Beauchamp was a member and indeed the King’s

victory at Agincourt was attributed to the aid given by that particular

saint. Richard himself had recovered

from an illness at the town of St. Albans, and St. Winifid of Wales was

the Patron Saint of the church in Shrewsbury

where he had received his Garter. Such was his devotion to these saints

that Beauchamp bequeathed a gold statue of

himself to each Monastic house patronised by these four saints, all of

which survive in their original

form. The manifestation

of this link can be seen in the words of the ‘Obsecro

Te’, a lengthy prayer to the Virgin contained within the Horea, which

Duffy maintains ‘quickly found favour with the

laity’. The final section of the prayer speaks of the benefits that

could be accrued through the intercessions of Mary.

Some of these could be enjoyed during earthly life but by far the

greatest was ‘the spiritual gifts a

Christian requires to get to Heaven’. For, if Christ is really judge

and arbiter at the end of time, who better than his Mother to

intercede for a human sinner. Therefore it is hardly surprising that

the effigy of Beauchamp lies with his hands

slightly apart so that he can clearly see the figure of Mary looking

down from a boss in the ceiling above his head.

The manifestation

of this link can be seen in the words of the ‘Obsecro

Te’, a lengthy prayer to the Virgin contained within the Horea, which

Duffy maintains ‘quickly found favour with the

laity’. The final section of the prayer speaks of the benefits that

could be accrued through the intercessions of Mary.

Some of these could be enjoyed during earthly life but by far the

greatest was ‘the spiritual gifts a

Christian requires to get to Heaven’. For, if Christ is really judge

and arbiter at the end of time, who better than his Mother to

intercede for a human sinner. Therefore it is hardly surprising that

the effigy of Beauchamp lies with his hands

slightly apart so that he can clearly see the figure of Mary looking

down from a boss in the ceiling above his head. Yet it was not just

the spiritual realm that was featured in the

window. The traceries, still in their original form, contain not only

seraphims and the Gloria, but also scrolls or pennants

with the words ‘Louez Spencer – tant que vyray’. In addition Kibble

believes that the subject matter in the

lowest portion of the window was Beauchamp himself, flanked by his two

wives Isabella Despencer and Elizabeth

Berkeley, his son Henry, and his daughters Anne, Margaret, Elizabeth

and Eleanor. While pointing out that the

religious imagery should not be viewed as mere decoration but ‘visible

proof of the presence of saints and their

intercessory powers’, Roffey also acknowledges that the fabric of

chantry chapels was also intended to ‘create potent

symbols of personal and corporate prestige, piety and influence’.

Yet it was not just

the spiritual realm that was featured in the

window. The traceries, still in their original form, contain not only

seraphims and the Gloria, but also scrolls or pennants

with the words ‘Louez Spencer – tant que vyray’. In addition Kibble

believes that the subject matter in the

lowest portion of the window was Beauchamp himself, flanked by his two

wives Isabella Despencer and Elizabeth

Berkeley, his son Henry, and his daughters Anne, Margaret, Elizabeth

and Eleanor. While pointing out that the

religious imagery should not be viewed as mere decoration but ‘visible

proof of the presence of saints and their

intercessory powers’, Roffey also acknowledges that the fabric of

chantry chapels was also intended to ‘create potent

symbols of personal and corporate prestige, piety and influence’. These were to be

newly traced and pictured by another painter employed

by Prudde, and from these the stained glass was to be executed. As

little as possible of green, white and

black were to be used as these were considered inferior. Prudde himself

was to take charge of the glass when wrought

and set it up in the chapel windows. For this he was paid two shillings

a square foot – a very considerable sum

considering that the usual charge for glass was between 7d. and 1

shilling even for prestigious buildings. Indeed, the

elaborate windows given by Henry VI to Eton College only cost 1s 4d per

square foot. The final cost of the windows

was about £100.

These were to be

newly traced and pictured by another painter employed

by Prudde, and from these the stained glass was to be executed. As

little as possible of green, white and

black were to be used as these were considered inferior. Prudde himself

was to take charge of the glass when wrought

and set it up in the chapel windows. For this he was paid two shillings

a square foot – a very considerable sum

considering that the usual charge for glass was between 7d. and 1

shilling even for prestigious buildings. Indeed, the

elaborate windows given by Henry VI to Eton College only cost 1s 4d per

square foot. The final cost of the windows

was about £100. The tomb was placed,

in accordance with the tradition of the time,

close to, and immediately in front of the focus of power – the altar.

Roffey maintains that ‘Burial close to the altar

forged a connection with the mass and its implicit intercessory

efficacy and highlighted one’s tomb or memorial to those

participating in the mass’.

The tomb was placed,

in accordance with the tradition of the time,

close to, and immediately in front of the focus of power – the altar.

Roffey maintains that ‘Burial close to the altar

forged a connection with the mass and its implicit intercessory

efficacy and highlighted one’s tomb or memorial to those

participating in the mass’. Brindley posits

that

is it unlikely that the effigy is an accurate

portrait, and that ‘The armour is of a style first made in Milan more

than a decade after Beauchamp’s death, and so could not have

been his own.’ This may very well be so, yet the intricate details,

such as the raised veining on the hands

indicate a desire for a high level of accuracy. Perhaps the effigy was

based on a lost portrait of Beauchamp as a young

man, for it does seem to be a likeness of someone and a desire for

exactitude would resonate with the growing

desire at that period to represent accurate physical features. Whereas

in the Romanesque Art of the early Middle

Ages faces lacked individualism and were even interchangeable, late

Medieval artists, sculptors and painters

began to embrace the Gothic style which was beginning to portray

individual features. This gave rise to the

flowering of Renaissance Art. This puzzle is one to which a solution is

unlikely to be found.

Brindley posits

that

is it unlikely that the effigy is an accurate

portrait, and that ‘The armour is of a style first made in Milan more

than a decade after Beauchamp’s death, and so could not have

been his own.’ This may very well be so, yet the intricate details,

such as the raised veining on the hands

indicate a desire for a high level of accuracy. Perhaps the effigy was

based on a lost portrait of Beauchamp as a young

man, for it does seem to be a likeness of someone and a desire for

exactitude would resonate with the growing

desire at that period to represent accurate physical features. Whereas

in the Romanesque Art of the early Middle

Ages faces lacked individualism and were even interchangeable, late

Medieval artists, sculptors and painters

began to embrace the Gothic style which was beginning to portray

individual features. This gave rise to the

flowering of Renaissance Art. This puzzle is one to which a solution is

unlikely to be found. Around the sides of

the tomb were set niches containing fourteen

figures or ‘weepers’ interspersed with angels and miniature bears and

ragged staffs. The figures were cast by William

Austen of London in latten, an alloy similar to bronze and covered in

gold. Weepers were living people who would mourn

the death of the person in the tomb and whose intercessions could add

weight to those of the saints. On one

side of Beauchamp’s tomb are female weepers and on the other side are

male weepers – all of them notable

members of Beauchamp’s family and the nobility, and each identifiable

from the enamelled coats of arms around

the base.

Around the sides of

the tomb were set niches containing fourteen

figures or ‘weepers’ interspersed with angels and miniature bears and

ragged staffs. The figures were cast by William

Austen of London in latten, an alloy similar to bronze and covered in

gold. Weepers were living people who would mourn

the death of the person in the tomb and whose intercessions could add

weight to those of the saints. On one

side of Beauchamp’s tomb are female weepers and on the other side are

male weepers – all of them notable

members of Beauchamp’s family and the nobility, and each identifiable

from the enamelled coats of arms around

the base.